Some articles and resources about computer chess go to great lengths in discussing Internet chess sites, places where you can play chess online. This article, however, won’t be one of them.

This omission is deliberate, as online play at its core isn’t terribly different from face to face chess. Subtract the players’ faces, substitute a 2D representation of a chess set, use a mouse instead of your hand, and it’s pretty much the same.

Likewise I’m not going to go into minute detail about how to play a game against your chess software program. The first thing everybody does within five minutes of finishing the installation of a chess program is play a game with the danged thing. I did it, you did it, there’s no point in mentioning that you can play chess with a chess program.

What I want to do is show you how to better use your chess program’s playing functions. Right off the bat I’ll tell you that it is completely pointless to play against a chess engine at its full strength.

Unless you use one or more of the well-publicized “anti-computer” tricks which is, again, pointless when it comes to your development as a player, when you play against a chess engine at its full bore strength, you lose. Many programs offer to let you limit a chess engine’s strength by setting casual time levels like “5 seconds a move”.

If you’re an average club level player, you’ll still lose. At five seconds a move, most chess engines running on current hardware will look ten to sixteen plies (five to eight full moves) ahead within one second of the time they start their analysis.

So why would you want to buy a mega-strong chess engine if the infernal thing is just going to tear your head off in a straight-up game? For its analysis features, of course, which we’ll learn about later.

There are plenty of resources around, and most of them are a waste of your money being as the point of owning a chess computer isn’t to beat it, but to use it as a tool. But, for those who would be disappointed if I don’t at least mention the topic…

How To Beat The Computer In Chess

Here is how to beat the computer in chess:

- Keep the position closed

- Keep the central pawns locked

- Avoid exchanging you central pawns

- Start with 1.d4

- Use your positional knowledge to maneuver to good squares

- launch a Kingside pawn storm straight at the opposing King once the center is closed

- Swarm in with your heavy pieces and checkmate the silicon monster

There are a lot of ways to beat a chess computer, all based on playing to your own strengths as a human while capitalizing on the computer’s well publicized weaknesses.

First, there’s the “general” method. Chess engines love wide open positions with lots of mobility for the pieces, and the danged programs can always be counted upon to crush you tactically in just such positions. So the first thing you need to do is keep the position closed.

Keep the central pawn position locked up and avoid exchanging off those center pawns. Openings that start with 1.d4 are especially good for this. It’s even easier if you’ve studied strategy and positional chess, since computers tend to stink at long-range planning.

Block the center to keep the computer cramped, then use your positional knowledge to maneuver, maneuver, maneuver, getting your pieces (especially your Knights) to good squares.

After you’ve ensured that the center will stay blocked (especially if the chess engine has moved a lot of its pieces to the Queenside), wait for the computer to castle Kingside (which it will do most of the time, unless its opening book directs otherwise), and then launch a Kingside pawn storm straight at the opposing King.

Make sure your pawns are backed up by your heavy pieces. This is especially effective if you’ve studied pawn structures and other general pawn play.

After the breakthrough, when files are opened, swarm in with your heavy pieces and checkmate the silicon monster.

It’s that simple. I know average club players who can do this at will against many chess engines, especially older programs. In recent years, programmers have improved their engines so that this technique isn’t the “insta-win” that it used to be, but it can still be pretty effective.

Alternate Methods of Beating The Chess Computer

There are more complex ways to beat your computer. If the chess program you bought gives you the ability to look at the engine’s opening book (also known as the opening tree), you might be able to discover a “hole”, a variation which is bad for the computer but which (due to an oversight on the programmers’ part) the engine will always play. I can still remember when a 1300 Elo player found just such a bad variation in the opening book of an early version of the Fritz program.

After 1.d4, Fritz (as Black) would invariably fall into this same hole, which allowed the human player as White to block the center, launch the Kingside pawn storm, and win (exactly as I described earlier). I checked the opening book and, sure enough, there was a hole.

The next version of Fritz fixed the hole, and the version after that added a feature which made the engine stop playing openings at which it kept losing. So this method isn’t as easy as it used to be, but you can still try it.

The first version of Fritz would always play the best move it found, no matter what. That meant that if the best move caused a draw by threefold repetition of the position, the engine played it anyway. I got a couple of easy draws that way when playing it. Later versions fixed that problem by allowing the engine to play the second-best move as long as that move was evaluated as being pretty close in strength to the best move.

Many chess engines have this feature programmed into their algorithms including Stockfish, Deep Blue and the famous Alpha Zero. However, you still occasionally come across a chess program which will draw this way (even if it’s winning materially). That brings us to another method, which is a bit more tricky to execute.

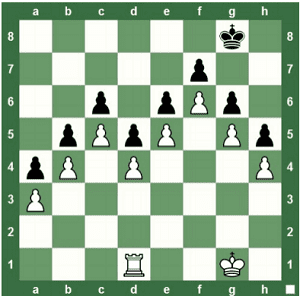

Have a look at this position:

White’s a Rook up in this position. Big deal. The game is a draw: the pawns are locked, the Kings can’t get through, and neither side can make progress, so White’s extra Rook doesn’t mean a blessed thing. But set up this position in your chess playing program and let your chess engine analyze it; I’ll bet you dollars to donuts that it’ll evaluate this as a winning position for White.

Computers do occasionally misevaluate a position, this position being a famous example. There are ways for a good player to exploit this tendency and win a game (or at least snatch an occasional draw), but it’s a bit tricky for the average chess player to execute.

So there are ways to beat your chess computer at its full strength (these are just a few). If all you want to do is beat your chess engine, have at it. But I’m going to move on now and talk about ways to use your program’s engine as an effective sparring partner to help you improve your own chess.

Post you may like: 15 Important Life Lessons From Chess

When it comes to computer chess, “handicap” is not a nasty word.

Since your chess engine will likely crush you like a bug on a windshield when you set it to full strength or even limit its thinking time to a second or two, how can you use it as a sparring partner?

Any chess playing program worth its salt these days will give you at least one mode (and usually more) in which you can get a competitive game without you being smashed up by the machine. Different software programs use different methods to accomplish this, and we’ll look at a few of the most common.

The important thing for you to remember is that there’s no shame at all in playing against a chess engine at a reduced strength level. In fact, you’re foolishly wasting your time if you don’t use these levels.

Back in the day, when a 386 25MHz processor was a miracle of computer science, you could set a casual time setting of, say, five seconds a move and stand a reasonable chance of doing well against a chess program. The engine would look only a move or two ahead during that time. They were still tough for an average Joe or Jane to beat since they pretty much saw everything out to that depth (you couldn’t surprise ’em), but you at least had a shot at winning.

But those days are long gone; as we learned earlier, most engines today do a relatively deep search in one second or less. When you’re trying to get a competitive game with a chess engine without being killed, the first thing to do is check your program’s documentation: the help files or a physical manual. While paper manuals are becoming a rarity, many chess programs offer a manual as a .pdf or .doc file somewhere on the disk; check the disk for a folder called “DOCS” or “MANUAL”.

When all else fails, the F1 key is still the universal computer “S.O.S.” call; hitting it will usually bring up a help file. Check the help file or manual for a section on “handicap” modes or reduced strength levels offered by the software. These easier play modes usually take one of a number of forms.

1. Adaptive Play

The chess engine will, over time, attempt to change its strength to more closely match yours. The result of each game you play against the engine will help it to more closely align itself with your level of play until you are winning 20% to 25% of your games against it. While that number might not sound especially high, many experienced chess coaches will agree with that percentage as the “golden ratio”, at which a student (i.e. you) loses often enough to promote the desire to learn and improve, but wins often enough to not become demoralized.

The old Power Chess program was the first to use such a play mode, but a few other chess playing programs have introduced this feature down through the years.

2. The “tactics seeker”

The playing programs produced by the German company ChessBase (Fritz, etc.) feature a mode in which the engine will look for tactics that you can play against it during its search and, when it finds such a possibility, steers play toward that position instead of away from it (as it would in a normal play mode).

If you wish, the program will also flash a light on the screen to alert you of a tactical maneuver when you have a move that will create one in the present board position. The feature puts to rest the common concern among chess players that “you can study tactics all day long but you’ll never get to use them against a computer”.

3. Pre-programmed “personalities”

These can be really cool to use if your chess program has them (I say “can be” because I’ve seen the idea abysmally executed in a few programs), especially if the personalities have approximate Elo ratings. Many programs down through the years have offered this feature in varying forms. Kasparov’s Gambit named its personalities after historical figures (like Genghis Khan) but didn’t offer anything other than a name and a rating.

Power Chess contained various cartoon-like characters with a little bit of biographical information. Chessmaster 6000 (and every version since) has provided the best execution of the idea, with a name, a rating, a photo of a real person, a little bit of personal information, and a capsule description of their chess tendencies.

Some programs, though, offer nothing but a one or two word description or, worse, fake the feature; one program from the 1990’s offered a variety of “opponents” who would move and speak, but they all played chess the exact same way. The point of a program’s suite of personalities is to “hook” you into playing more chess by (at least on a subconscious level) making you think you’re playing people at a simulated chess club, and it’s often pretty effective; I had a lively “virtual rivalry” with one of the Power Chess characters many years ago. I’ll offer some creative ways of using personalities later.

4. The Elo rating slider

The “old standby” which is a part of nearly every commercial software program released in the last decade or so. The software offers a slider which you can adjust to make the program stronger or weaker; moving the slider also displays the approximate rating at which the program will play.

These numbers are rarely exact, since a rating is just a benchmark of your expected performance against a specific opponent, based on your prior performance within a closed pool of players. Translated into English, that means that you as a player can actually have widely different ratings at the same time: one for your real life tournament games, one for correspondence games, one assigned by playing rated games against a chess computer, and one for every single online chess site at which you compete, and these may or may not even be close to each other.

So any rating offered by a chess program, whether assigned to a “virtual” personality or the position of a rating slider, is an approximation at best. We’ll be discussing this feature a bit later in this chapter, because it’s almost a “universal” feature and is very useful for the average player.

Quite a few chess programs also allow you to adjust the engine’s play according to specific criteria, such as aggressiveness, defensiveness, King safety, and central control, as well as to tweak the engine so that it might prefer certain chess openings or move some pieces more than others.

I’ve used these features successfully in the past to roughly simulate the play of a few of my real life chess club opponents, but it’s largely a matter of trial and error, and you have to be dang near a cross between Claude Shannon and Mikhail Botvinnik to get it just right on the first try.

But I do encourage you to look for and play around with such features in your favorite chess program.

Related Post: How do Chess Engines work?

Trick yourself into playing more games

Nothing motivates a chess player like a good rivalry. Back when I started playing this game seriously (meaning I started spending a truly ridiculous amount of time playing and studying chess as my primary hobby), I had the misfortune of playing with a casual group of guys who were, by and large, buttheads. They’d usually win and, instead of offering advice on how to improve my play, would typically toss off a snotty remark about how bad a player I was.

Now while I don’t recommend that you go out and find a bunch of jerks to play chess with, I will tell you that the desire to give these guys a comeuppance was a great motivator which spurred my desire to improve my chess play. And, having improved to the point at which I was regularly beating these guys although I didn’t act like them after I’d win, I will tell you that whoever said revenge isn’t sweet didn’t know what the heck he was talking about.

So ultimately what you want to do when playing with your favorite chess program is to find some setting which challenges you without completely crushing and humiliating you. The idea is to find a setting at which you will win around a quarter of the time.

If your particular program doesn’t offer an adaptive opponent which will do this for you, then you’ll need to take the bull by the horns and figure out how to find or create a setting which provides this level of challenge.

It’s easy to do this with a program that offers pre-programmed rated personalities. The easiest thing to do is pick an opponent whose rating is about a hundred points higher than your own (assuming that you’re a rated player) and start playing some games. If you’re not a rated player, pick a personality as a starting point, then adjust your choice up or down the player list according to how well or poorly you do.

Ultimately, you need to try tricking yourself into thinking you’re playing a real person. I don’t mean in some psychologically unbalanced way in which you become obsessed with this non-person, but in a healthy way in which you want to become a better player so that you can beat this imaginary character. And doing so can provide a pretty healthy impetus to your growth as a player.

As I mentioned earlier, one of the Power Chess characters became my imaginary rival for quite a while (primarily because of its opening choices, which took me into variations which none of my real life sparring partners ever played). The “hook” was the fact that the character had a name and a (cartoon) face; I doubt that I would have been nearly as eager to beat this character had it been just a group of settings and sliders.

Establishing a rivalry with a particularly tough to beat personality, setting, or level in a chess program is a great way to make yourself want to play and study more chess. It’s a “virtual” rivalry, but without the snide comments and bad feelings you might be subjected to if you were playing against a bunch of jerks (the kind I had to play back in the day). Best of all, if you have a hard time beating an imaginary guy named “Toby” from a chess program, nobody knows except you and “Toby”, and I greatly doubt old Toby much cares either way.

Post you may like: Are Chess Players Smart?

Set up a tournament and play

One of my favorite “tricks” when using chess programs with rated personalities was to play in “fake” tournaments. A popular tournament format is called a “quad”, in which all of the players are ranked in order of their ratings, then divided into groups of four players. In theory, each player in a four player group should be fairly close to the others in rating; each group has a round-robin “mini tournament” amongst themselves, in which each player in the group plays each of the other three players once (and, if you do the math, each player will thus play three games, resulting in the combined number of games for the event being twelve).

Note that this approach only works well if your chess program lets its personalities play against each other (some don’t). The Chessmaster series did allow the user to set up games between personalities, so that program was frequently my choice. I’d scroll through the list of characters and pick out three of them: two who were a bit more highly rated than my real life rating and one whose rating was a bit lower. I’d then randomly pair the first round by writing down the other three players’ names and picking one out of a hat, then flipping a coin or rolling a die for choice of color in my game.

I’d play my game against the first personality, save the game afterward for later review, then let the other two personalities play out their game. I’d repeat the process for three rounds, trying my best to alternate players’ colors from round to round.

If I did well in the tournament, I’d drop the low rated player in the next “virtual” event I ran. I’d keep the other two players the next time and add the next higher rated player from the program’s full list to replace the character I’d dropped. But if I did poorly in the event, I’d drop the highest rated player the next time and instead play against the other two players plus the next lowest rated player from the list.

If I felt especially ambitious (as I often did back then), I’d use the Elo rating formula to calculate my new “virtual rating” after each event and keep track of that from tournament to tournament as an extra incentive to keep studying and improving. I can tell you from personal experience, this was not only a great way to “trick myself” into constantly trying to improve, the games I played also gave me more information about what I needed to study in order to make that improvement happen. Best of all, playing in these “virtual tournaments” is also a whale of a lot of fun.

Oh it’s on now! Playing one on one matches

Another great method to spur yourself to play is to set up and play one on one matches against your chess engine. While this method works with a pre-programmed personality, it’s a method you can easily use if the only thing your program of choice offers is a rating slider. In fact, a rating slider is ideal for this method, as we’ll soon see.

If you’re a rated player, set the rating slider to your own rating as a start; round your rating up if the slider can’t be set to your exact rating (for example, 1635 might be rounded up to 1650 if the slider only recognizes fifty point increments).

You’ll now play a six game match against the chess engine set to at that rating. Obviously, you don’t have to play all six games at one sitting; in fact, it’s best that you don’t so that you’ll have time to analyze each one of your games afterward, before the next game (more about that later).

It’s important that you alternate colors each game, so that you’ll play exactly three games each as White and Black, switching colors from round to round. That’s how a real chess match is played, so you should follow suit. And you’ll score the results just as you would a real life match: you earn one point for a win, no points for a loss, and a draw scores a half-point for both you and your virtual foe (in other words the two of you split the point).

The result of your six game contest will determine your next virtual opponent. If you win the match by scoring at least 3.5 points, move the rating slider up to the next highest increment (I suggest by a minimum of twenty-five points) and then start another six game match. If you lose the match, lower the rating slider to the next lowest increment (I again suggest a minimum change of twenty-five points if possible) and play a new six game match against the engine at that setting. If you tie the match (3-3), leave the slider where it is and start a new match.

In this manner you’ll advance when you win and get knocked back a step when you lose. Obviously you’ll want to win so that you can face greater challenges. If you spend more time playing chess than you spend studying, you’re likely to “settle in” to a point at which you’re bouncing up and down across a 100 or 150 point span. That’s natural and very much like the situation you’d find at a real chess club, in which you often prefer to play three or four other players who are around your own playing strength.

But, just as in real life, you’ll want to study and improve so that you can play against other players; ultimately, when you work hard enough, you’ll break out of that rating “plateau” and move up to greater challenges. You can do this same thing quite easily with pre-programmed personalities in a chess program, moving up to the next higher-rated character when you win a match or down to the next lowest personality when you lose.

And when you eventually “settle in” (as we saw in the last paragraph), this will be very much like a real chess club, as you’ll likely be seeing the same faces on your screen again and again; the desire to “play someone new” will spur your desire to improve. Just like the “virtual tournament” idea, the “home chess match” works really well. I’ve used both methods successfully and had a lot of fun doing it!

By the way, it’s up to you as to whether or not you want to play timed games in either of these modes I’ve suggested. It’s not a requirement to do so, but if you’re one of those players who always finds himself in time trouble in real life games, I heartily recommend that you use the clock

To rate or not to rate? That is the question

Most chess programs offer a “rated game” mode, in which you play against the chess engine under simulated tournament conditions (timed game, no pausing the clock, no move takebacks, no hints, alternating piece color from game to game, etc.). But should you play rated games against your computer?

It’s up to you, and depends in large measure upon what your particular chess program offers you. Some chess programs provide a rating slider so that you can choose the approximate strength of your opponent. The stronger the opponent, the more rating points you earn for a win and the less you risk for a loss.

However, some programs’ sliders will only go down to a certain point in a rated play mode. If your program’s lowest rating setting is several hundred points higher than your actual tournament chess rating, I see no point in even bothering to play a rated game which you have little chance of winning. Note that many programs allow the use of “modular” engines, meaning that you can “unplug” one chess engine and use a different one instead.

Different engines usually provide different ranges of ratings, so you might want to try multiple engines to see how the ratings differ. But if you’re a 1400 rated player and the lowest rated game level is 1850, there’s not much point in playing around with it. You might win, or course, but since most programs won’t offer an “official” rating until many games (usually twenty) are played, the exercise may not have much of a point.

On the other hand, some programs do allow the slider to go quite low; for example, Chess King’s rating slider can be set as low as 700 Elo. In this case, you might want to play a lot of rated games against a variety of opposition levels. I suggest that you try the rating slider in several casual games to get a feel for the difficulty before launching into rated games. Programs like Chess King will always display your rating as part of your on screen user profilewhich might encourage you to try raising your level (especially since every player starts with a default rating of 800, which is very low).

My friends are perfectly happy to play mostly unrated games and seem unconcerned about their on screen ratings, worrying more about who has “leveled up” past them. Bear in mind that the rating you earn in your games against any chess software program are nothing more than a measure of your performance while playing that program, and may have nothing to do with any rating you may earn using another program, playing online, or competing in tournament games.

The choice is yours. You shouldn’t feel like you must play rated games against a chess engine, but the option is there and you can often learn a lot about your play from games when you don’t have access to takebacks, the engine analysis panel (to see what the engine is thinking), or other hints.

Beat the Clock

Likewise some people might question whether or not using a chess clock is strictly necessary. Some play modes, such as rated game mode, might require the use of a clock. I’ve also seen programs which require that a clock be set and used, but don’t penalize overstepping the time limit in casual (non-rated) games against the computer.

As with rated games, it’s your choice. But I will recommend one case in which a chess clock should always be used by players who habitually and regularly find themselves in time trouble. I’ve played scores of tournament games and have only found myself in time pressure once or twice. On the other hand, I have friends who’ve practically made a whole career of it. The time control makes no difference. Game in 30? They’re in time pressure. Forty moves in two hours? They have four minutes left on the clock and they’re only on move twenty-eight. It’s completely ridiculous.

Assuming that you’re not some kind of subconscious “adrenaline junky” and quite literally can’t and will never be able to help yourself because you positively crave that rush, you can use your chess program’s timed modes to break yourself of the habit. And it’s easier than you might think. All you have to do is set the clock for a shorter time limit than that of the tournaments in which you normally play.

The method works, too. I used to direct tournaments which were run at “game in sixty minutes” time controls. So for the week leading up to a tournament, I would play all of my practice games against the computer at “game in forty-five”.

Bear in mind that I was never one to usually get in time trouble anyway, but I found that playing at this slightly accelerated pace helped me in tournaments. I always had extra time whenever I needed it.

In fact, in most of my games I had well over five minutes on the clock when the game ended. So if you’re one of those unfortunate souls who seems to always be in time pressure, use your computer chess software as a tool to help you break the habit: play faster games at home than you do in tournaments and, after a while, you’ll discover that you seldom end up in time trouble anymore.

Save your computer games always!

Always, always, always save the games you play against your chess computer! Reviewing and analyzing them later will provide you with bucketloads of valuable information on how you can improve. Only complete fly-by-night cheap junk chess programs don’t allow you to save your games after you play them; in fact, most chess programs these days will save your games into a default database automatically.

The only real issue to discuss here is what format to use when you save your games. Many chess programs can save games into some proprietary file format, that is, a format that can be read by that particular program.

Nearly every program, though, will save your games into a format called PGN, which stands for Portable Game Notation (“portable” meaning that the game can be ported [carried] from one program to another).

A PGN file is just a glorified text file (you can easily open it in a word processor and read the game score) in which the information’s formatting, such as game headers and move spacing, follows a set of strictly proscribed rules.

Each format has advantages. Saving a game in PGN format means that you can play a game in one program, save it, and then open it up and analyze it in a different program. Proprietary formats usually allow additional game annotation (comment) features, like colored arrows or pop-up windows showing a position’s pawn structure, features which can’t be used in a PGN text file.

Consider the options and make your pick but, either way, save your games!!!

Final Verdict – How To Beat The Computer In Chess

There are just a few basic ideas you should take away with you after reading this article:

- Playing a chess computer at its full strength is pointless.Find a level at which you win about a quarter of your games (if your chess program doesn’t offer such an adaptive opponent).

- Play as much chess as you can.If you have to, find ways to “trick yourself” into wanting to play more chess which also help you measure your progress as a player such as the “virtual” tournaments and matches I suggested.

- And always save your games!