In order to play chess like a grandmaster, you first have to develop a system of thinking. Most grandmasters have a sophisticated thought process. In fact, this same thought process is commonly used by the massive of so called super gm’s. It involves two things:

- Progressive Thinking

- Reciprocal Thinking

As you read further along, you will learn in details about these two systems of thinking and how it is allowed many average players to really dominate in their games. Without further ado, let’s discover how to think like a chess grandmaster.

Grandmaster’s Progressive Thinking

Progressive Thinking is one of the most common thought process that most grandmasters possess. A grandmaster will rely on this system of thinking to find the best move on the chess board, especially when dealt with complicated positions and sharp lines. By mastering this way of thinking, you will find significant improvements in your games which will lead to more confidence over the board for many games to come.

4 Steps to Progressive Thinking

A lot of chess players are faced with tough decisions over the board and are sometimes confused on what to do, which can lead to nervousness, creating blunders and running into time trouble.

What should I undertake? How am I to continue? These are the questions which chess players are faced with at every turn. To answer them correctly, you have to perform a specific task which compromises a number of steps. Follow these steps correctly, and you’ll be on your way to mastering progressive thinking:

Step 1: Study the position

The first step to finding the right move in a chess game is to “study the position”. To assess or study a given position, you have to identify all the tactical and strategic peculiarities of the configuration of pieces and pawns. This is what every grandmaster does first before even beginning to calculate variations.

Note the word study. We are not talking about “evaluating” the position but about “studying” it, because an evaluation just by itself (without study) doesn’t supply the key to further action. For instance it may be a case of “White stands better”, and a young player may give the correct assessment. However, he won’t know what to do next. What is he to do with this “better” position?

Nevertheless, here are the key guides to follow when assessing/studying a position. Look for:

Pawn Structure: A good pawn structure depends on the connectivity of your pawns to form what is known as a pawn chain. Isolated pawns, backward pawns and doubled pawns are all examples of a bad pawn structure because they are easy targets of attack.

King Safety: A castled king is usually safer than an uncastled king. This is because it is further away from the action and threats of enemy pieces. Also, pushing the pawns that helps to protect your king generally causes weakness around your king which can be exploited by an enemy piece.

Activity of Pieces: This is by far the most important factor to look at when studying a position. Activity in chess simply means the number of squares your pieces have control over. The greater the number is the greater your influence and control over the board. If you want to play like a grandmaster, then the activity of your pieces should be in the forefront of your thought process.

Space: This goes in relation to activity. To gain more space means that you have greater control over more squares than of your opponent. And to do this, you must advance your pawns further up the board. This will in turn increase your activity and at the same time limits your opponent’s activity.

Light and Dark squared Weaknesses: You know when you have weak squares when there are no pawns nor pieces covering them. For example, if you should fianchetto your light squared Bishop on the kingside and later in the game it gets exchanged for the opponent’s counterpart, then you have what is called light squared weaknesses around your king. It’s a weakness because there is hardly enough protection over these squares.

Loose pieces: Most grandmaster’s look for or even create weaknesses for their opponent. However, another important aspect that grandmasters seek to identify are loose pieces roaming in enemy camp. Like weak pawns, loose pieces are unprotected and can be exploited through tactics.

Now that we know the basis on studying a position, let’s move unto the next step of progressive thinking.

Step 2: Select Candidate Moves

We’ve studied the position keenly and have gotten a thorough knowledge of the pros and cons of both sides. But what are we to do next?

Well, that all depends on how thoroughly you assessed the position. Studying the position carefully (based on the factors I mentioned previously) will inevitably allow you to generate ideas with their corresponding “candidate moves”. So if you assessed the position poorly, then chances are your next set of moves will be not too good.

Most grandmaster have an average of 3 candidate moves after carefully assessing the position. These ideas aim at exploiting some particular characteristics of the situation.

The best candidate moves are the ones that are attacking. What this means is that you should look for checks, captures and attacks. This follows the general principle of attack which states that you must attack on your every move. Of course, not all attacks will work and so this leads us to our next steps…

Step 3: Calculating and assess the position

After selecting your candidate moves, it’s time to now calculate the variations for each move and asses the position to which they lead. In other words, way up an idea and asses it for suitability. Of course at the end of each line, you’ll assess the position based on factors I mentioned such as activity, pawn structure, weaknesses, king safety etc.

If you still haven’t gotten around the word “calculate”, then it simply means to find all the possible moves your opponent can play once after you made your move. You may wish to calculate up to 4 or 5 moves ahead which is pretty good for the average player. Most grandmasters in the big leagues can calculate up to 10 moves ahead. The more moves is the better!

Don’t worry, once you solve a lot more chess puzzles you’ll begin to see a positive change in your calculation abilities.

Step 4: Make your move!

If the verdict on the idea is positive, you carry it out, that is you make the corresponding move. Once you calculate a candidate move and the assessment is positive for your side, then their shouldn’t be any hesitation to go for that move.

Applying progressive thinking in your chess games

Let us take an example of which all 4 steps of progressive thinking were made during a game.

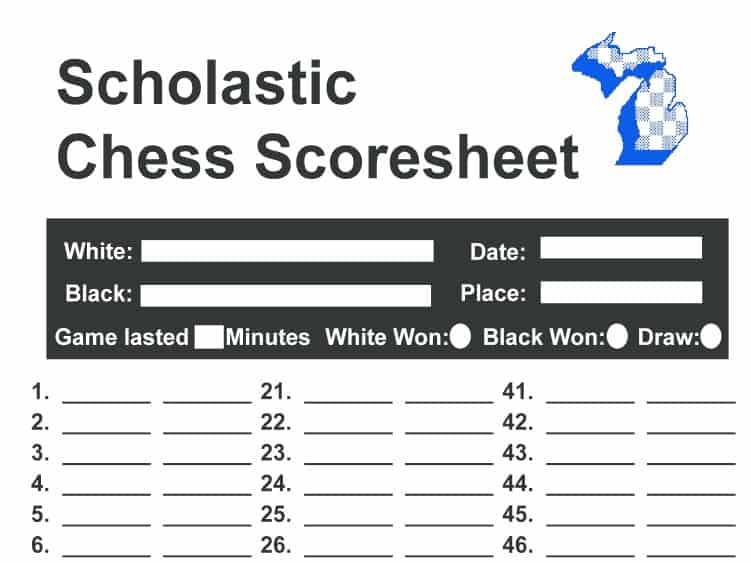

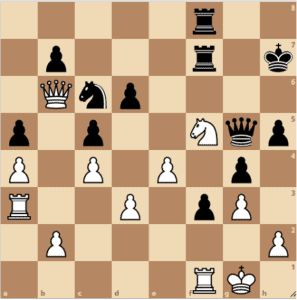

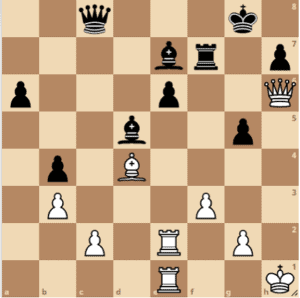

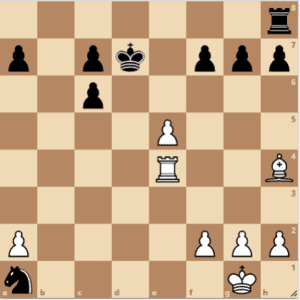

Toshkov-Russek

Saint John-1988

White to move

Studying Phase:

As we study the situation, our attention is drawn to the following:

- Of the tactical features we notice the opposition of the queens, and the fact that the bishop on d6 is to some extent “hanging”.

- The alignment of the king and bishop on the a2-g8 diagonal. This means that the pawn on f7 is pinned.

- Of the strategic factors we notice White’s pawn superiority in the center, and Black’s on the queenside.

Selecting candidate moves:

From the above study, some ideas and candidate moves emerge.

- White could try to pick up the bishop the bishop on d6 by jumping to b5 or f5 with a knight via 1.Ncb5, 1.Ndb5 or 1.Nf5.

- White could attempt to win the knight on g6 after clearing the pawn from e4, thus 1.e5.

- He could prepare the advance of his pawn e and f pawns with Nde2 or Qd2.

You might ask about the order in which the candidate moves should be examined. The answer is, first of all look at the most promising ones, those which are forcing and tactical in character as I previously mentioned (checks, captures and attacks). Only then examine the moves which aim to carry out a strategic plan. With that said let’s proceed to the calculation of variations.

Calculate Variations:

Candidate move #1: It’s clear that knight excursions to b5 promise nothing good, while 1.Nf5 doesn’t lead to a forced line of play, and would require detailed investigation. So we switch to the following possibility:

Candidate move #2: 1.e5, a fairly straightforward analysis shows that White wins. The verdict on the idea is positive and the move can be played. As you can see then, we never got around to examining the strategic moves 1.Nde2 and 1.Qd2. In the game, the continuation was: 1.e5! Nxe5 2.f4 (the knight perishes) …Neg4 3.hxg4 Nxg4 4.Bc1 Rad8 5.Ne4…1-0.

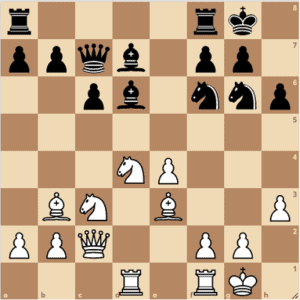

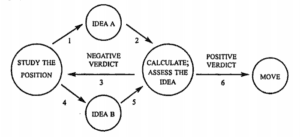

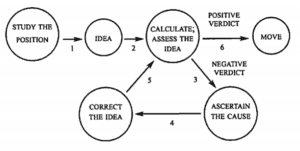

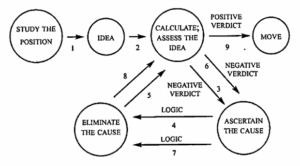

In case the winning idea was “on the surface”, the variations proved very simple and white didn’t need to dig deep. Finally, let us visualize this progressive way of thinking by many grandmasters as a road map to success:

Grandmaster’s Thought Process

But is what we have said above realistic?

Usually it all happens a bit differently. When a player turns his attention to the placing of the queens and the vulnerability of the bishop d6, and notes the corresponding moves 1.Ncb5 1.Ndb5, it’s hard to imagine him not looking immediately at the capture of the knight 1…cxb5. In other words, a preliminary, cursory inspection of the elementary forced variations takes place as soon as the idea emerges. In this way, idea A is discarded without further ado.

Next, the player will notice the opposition of the bishop and king, the pin on the f7-pawn and the unprotected position of the knight on g6. The move 1.e5 comes into his head, and he immediately starts working out the variations.

With this, the preparatory work is practically finished. The player will dispense with any further investigations. He will re-check his variations and play 1.e5.

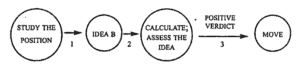

It’s easy to see that this scheme differs substantially from the previous one. If idea B cropped up first (as well it might), the scheme of thought would be simplified still further:

We will agree to classify this theme as progressive thinking, by which we mean a simple, straightforward train of thought. In chess as in life, battles are fought between ideas. As a rule, the more sophisticated ones prevail.

Related Post: 11 tips to get better at chess

Grandmaster’s Reciprocal Thinking

After noticing an idea and briefly familiarizing ourselves with it, we proceed to its detailed examination. What do we do if we find that it doesn’t work? Do we discard it and try another one, and then the next one and so on? Then do we come back to the first one, and study it more closely? This is hardly sensible.

If we fail to make an idea work, we need to stop and ascertain the cause of failure. In other words, answer the question “why?” and then attempt to correct our design. This form of approach is known as reciprocal thinking. Master it and you’ll be on your way to playing like a grandmaster.

Let’s take an example:

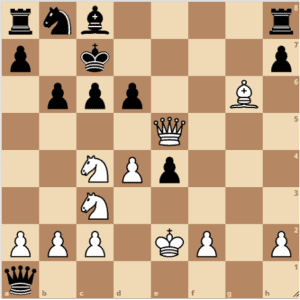

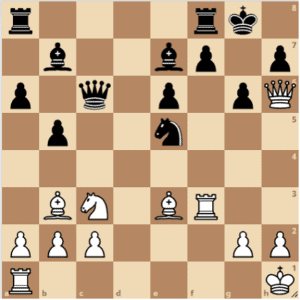

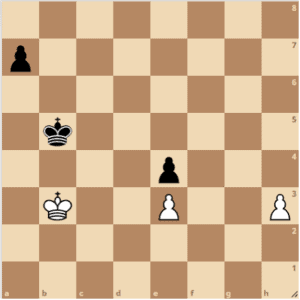

Gm Aronin – Gm Kholmov

Yerevan, 1962

Black to move

It’s interesting to acquaint ourselves with Kholmov’s comments: “Black’s advantage is undeniable. It looks as if 32…Nd4 would be very strong, removing the last obstacle the knight on f5. But then there could follow 33.Nxd4 Qe3+ 34.Kh1 cxd4 35.Qxa5, and White obtains saving chances based on the threat of perpetual check. This variation didn’t satisfy me, so my thoughts took a new direction. What about 32…Qd2? Then White evidently has to play 33.Rf2, to defend against mate. But after that it’s simple:

33…Qd1+ 34.Rf1 f2+! 35.Kxf2 Rxf5+ 36.exf5 Rxf5+ 37.Ke3 Qxf1, and Black wins.

“That’s it, I’ve found the solution let’s go!

“And yet just as my hand was reaching out towards the queen, an uneasy feeling came over me. On 32…Qd2, White has 33.Nh4! What then? Black would gain nothing from 33…Nd4, in view of 34.Qxd6. The threats of 35.Qg6+ and 35.Qxc5 would be quite unpleasant. After a little more thought I came to the conclusion that the knight on f5 had to be eliminated at once.”

32…Rxf5! 33.exf5 Qd2, and white resigned.

What did Kholmov do? He corrected his idea through reciprocal thinking. How? By altering the order of moves.

Let’s look at another episode in which reciprocal thinking is applied.

Purins – Inglitls

Correspondence game 1971

White to move

After 1.Qxd6+ Kb7, or 1.Nxd6 hxg6, no decisive continuations are to be found. What is White to do?

1.Nb5+!! An important interpolation, With this intermediate check, White causes the long diagonal to be opened, allowing his bishop to join in the attack with tempo: 1…cxb5 (or 1…Kb7 2.Ncxd6+ Ka6 3.Nc7 mate) 2.Qxd6+ Kb7 3.Bxe4+! Nc6 4.Bxc6+ Ka6 5.Qa3 mate. Therefore Black resigned.

By inserting a useful intermediate move, White brought about a favorable change in the position. Thus an idea may be corrected by:

- Altering the order of moves

- Inserting an intermediate move

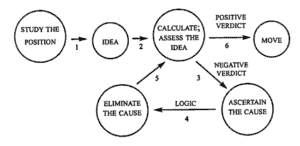

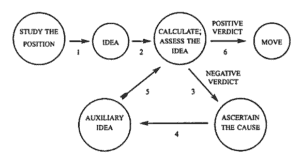

A simplified representation of the reciprocal scheme of thought would look like this:

A problem that many young aspiring grandmasters have is that they don’t think about the reason why one idea doesn’t work. They set about examining the next one straight away. In other words in the logical chain of their thought there is a link missing, namely “ascertain the cause and consequently correct the idea”.

This results in missed opportunities and a low quality of play. Experience has shown that the reciprocal manner of thinking is easy for a player to develop.

A grandmaster’s Reciprocal thinking can be further broken down into 2 constituents:

- Logic

- Auxiliary idea

Logic

Quite often a player succeeds in physically eliminating the reason why an idea doesn’t work. This is achieved with the aid of logic. This is achieved with the aid of logic.

Sax-Partos

Biel 1985

White to move

The straightforward 1.Rxe6 Bxe6 2.Rxe6 looks obvious, but then Black parries the threat of 3.Rg6+ by playing 2…Qxc2.

1.c4 bxc3 Now the queen can’t get to c2!

2.Rxe6 Bxe6 3.Rxe6 Bf6 4.Rxf6, and Partos resigned.

In this case, White eliminated the direct defensive possibility Qc8xc2

Let’s look at another example.

Bednarski – Ghitescu

Bath 1973

White can’t play 1.Rh3 because of mate on g2. 1.Bd5! Depriving Black of his counter threats on the long diagonal- a logical decision! 1…Nxf3 if 1…exd5, then 2.Rh3

2.Bxc6 Bxc6 3.gxf3 Bxf3+ 4.Kg1…1-0

Here White parried his opponent’s counter-threat with tempo, that is he deprived him of an indirect defence.

Sometimes more complex cases arises.

Lukin- Yuneev

Leningrad,1989

White to move

The knight on a1 is short of mobility. White can try to win it with 1.Rc4, but Black replies 1…Rb8 and saves his piece by exploiting the weakness of the back rank:

2.Rc1 Nc2! So let’s try to stop the black rook from coming into play: 1.Rd4+ Kc8 (the square b8 is now accessible) 2.Rc4, and wins.

However the king isn’t forced to retreat to the eight rank. Black has 1…Ke6. Well, can we deprive him of this possibility too?

1.e6+!! fxe6 2.Rd4+, and Yuneev laid down his arms.

In this case, how will the reciprocal train of thought be schematically represented?

Auxiliary Idea

Sometimes to carry out the idea, you need to find another auxiliary one.

Gulko – Vaganian

Reggio Emilia 1981

Black to move

Black is in a difficult situation. To save himself, he will have to the h-pawn (which is a log way away) and get back to the f5-square. But analysis shows that he is one tempo short. His position looks hopeless.

1…Kc5 2.Ka4 Playing 2.h4 would be silly. The opposing king is in the square.

2…Kc4!! The auxiliary idea! By threatening to take the e3-pawn, Vaganian forces his opponent’s next moves:

3.h4 After 3.Ka5 Kd3, the game would be drawn.

3…Kd5! Reverting to the original idea. The route to the h-pawn is now square shorter!

4.Ka5 Ke5 5.Ka6 Kf5 6.Kxa7 Kg4 7.Kb6 Kxh4 8.Kc5 Kg4! But not 8…Kg3? on account of 9.Kd5! Kf3 10.Kd4.

9.Kd5 Kf5 ½–½

Final Verdict – How to think like a chess grandmaster

To sum up everything, a grandmaster relies on two systems of thinking when playing a game of chess: one is progressive thinking and the other is reciprocal thinking. Progressive thinking can be mapped to a flow chart that yields a positive verdict.

It involves studying, calculating and assessing the position which all contributes to making the right to move in the game. Reciprocal thinking on the other hand is used to ascertain the cause of failure for an idea and thereby making the necessary corrections by altering the order of moves.

This is how grandmasters think and play during a chess game. It’s really no big secret. Now that you know the correct system of thinking in chess, it’s time to apply it in your chess games. Do this and you will definitely see drastic improvements in your games. Best of luck 🙂